Illuminated Wisdom: Buddhist Calligraphy & Verse

by Ajahn Dhammadharo | Feb. 1, 2023

On Calligraphy

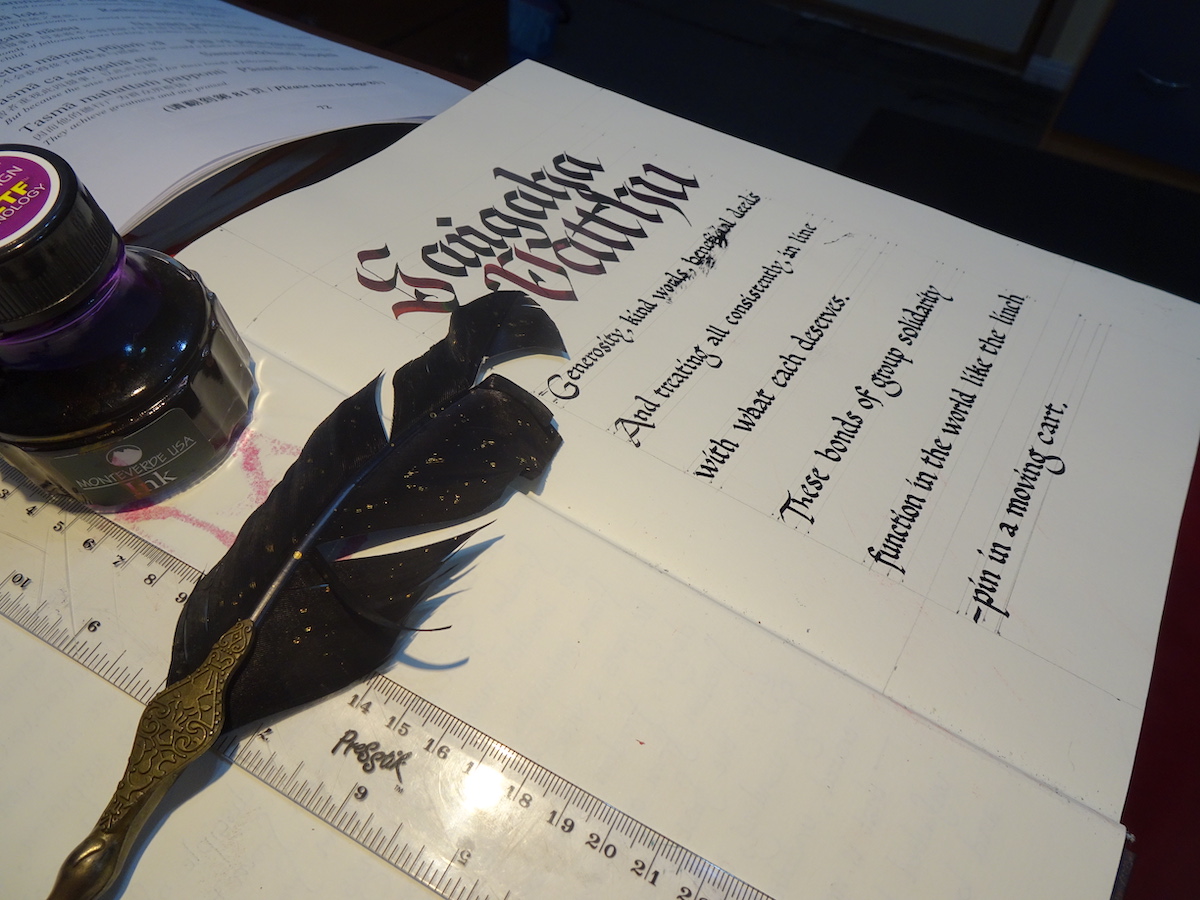

There is an old Thai maxim: “To inscribe one letter of Dhamma is equal in value to casting one statue of the Buddha.” We could interpret the word “inscribe” as an aged version of what might now be better—and more conveniently—interpreted as “write”. But the word used in the original Thai—jah-reuk—does literally mean “inscribe”. And it’s worth noting that to inscribe something is quite a different experience to writing. It takes much more patience, effort, attention to detail, and mindfulness—in a nut shell, much more care—than just jotting or typing.

And I’m not the only one to note that there is something more evocative and moving in the reading experience when words are written in someone’s own hand compared to what is generated by technology or automated by type-faces. It probably makes us feel that bit closer to the person behind the words; like what they are sharing with us is somehow more personal and authentic. This is because a person’s handwritten words are a direct and physical continuation of their own hand onto the page, with no artificial or digital tools between us and the writer. And surely, the potency of this can increase dramatically when the words are calligraphed.

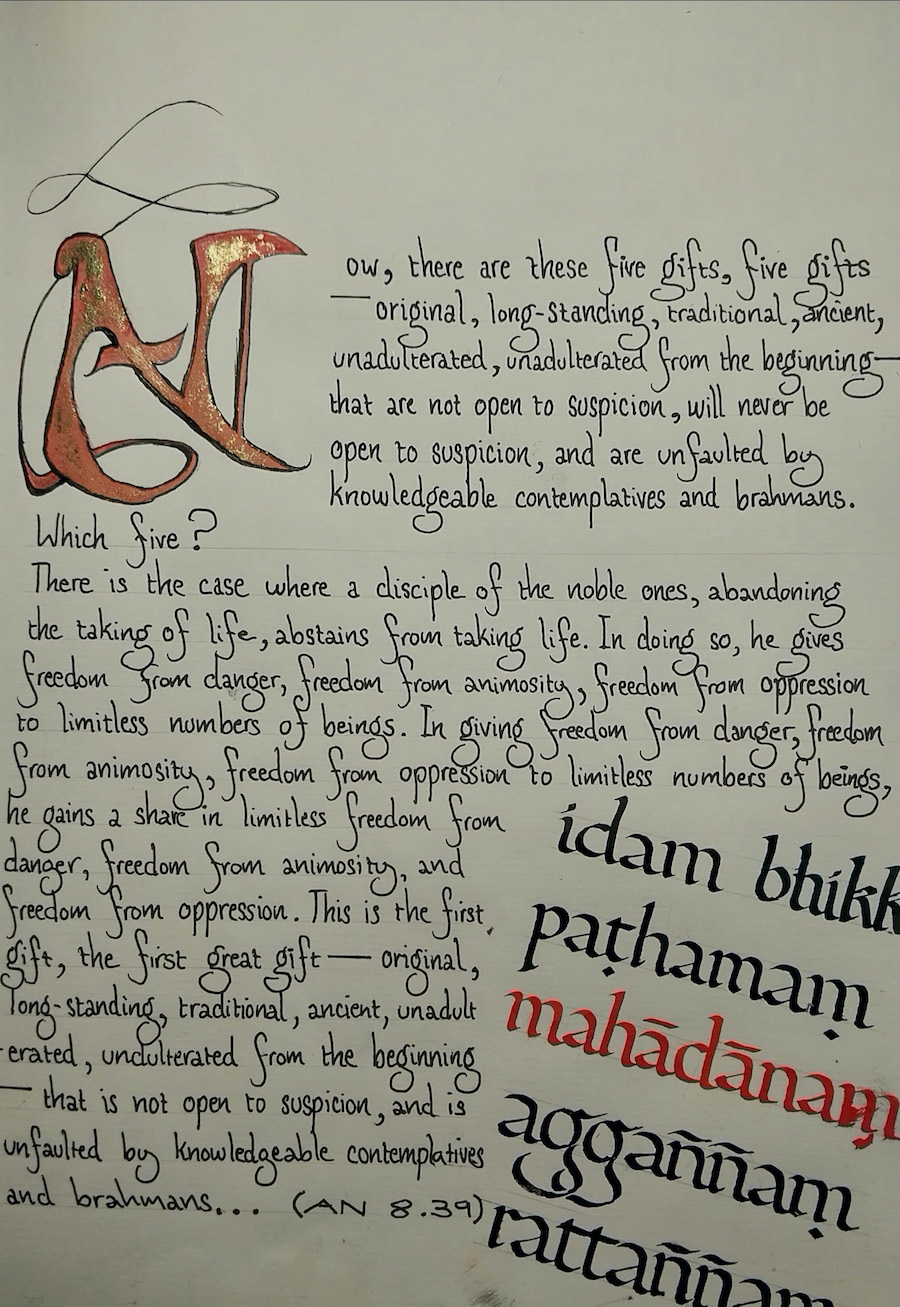

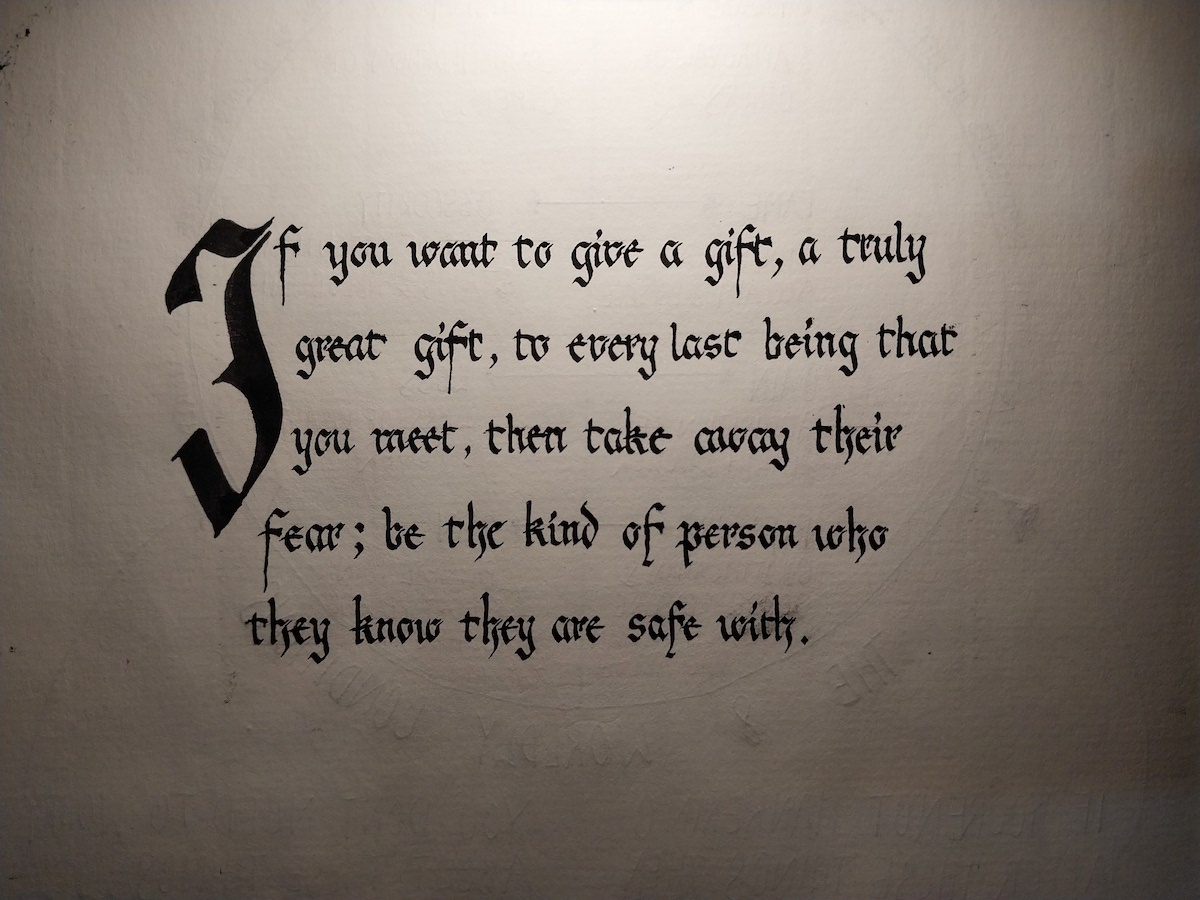

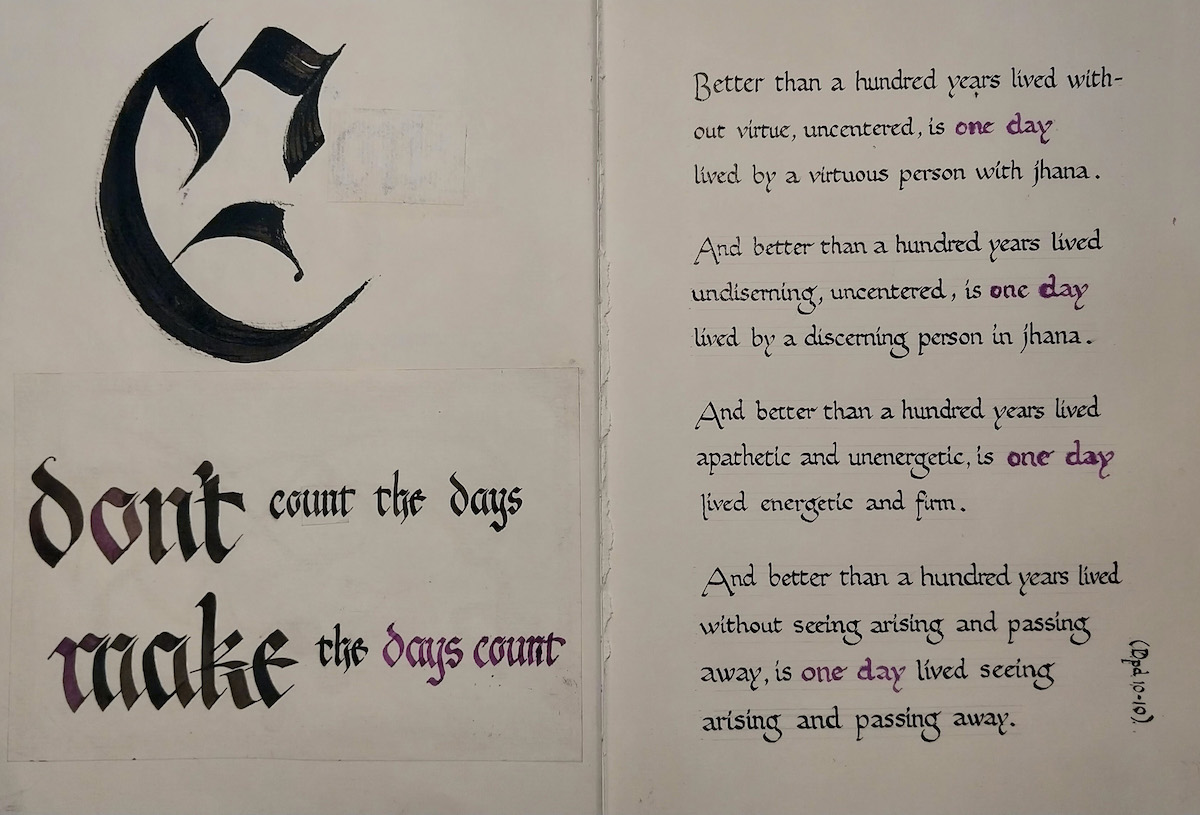

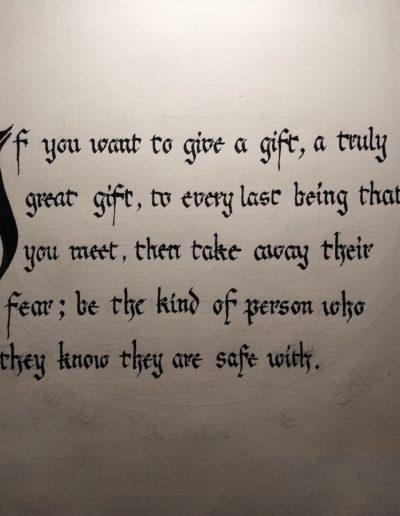

Calligraphy is a three-way intersection where writing, art, and wisdom meet and converge in a single discipline. This discipline or artform is one for people who love words with depth. Maybe this is the underlying reason why spiritual traditions, both East and West, have shared this practice through the ages; why people from many different countries have been recording their teachings through the scribal arts for thousands of years: They all feel a need to highlight and share their message with their quills, pens, and brushes in a way that makes it clear to the reader that these words are important. When scribes and calligraphers take the time to do what they do, the importance they are giving certain words is visible, sometimes almost mesmerizingly so.

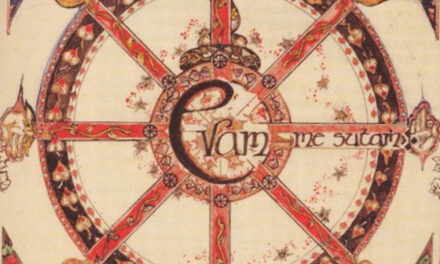

Something which is striking is the uncanny and longstanding connection between the pen and the robe. In Europe, it dates back at least as far as 6th century where the scriptorium, often a wing of the monastery library, was historically a place where you would find monks copying out texts, calligraphing and illuminating manuscripts, binding, and archiving. In short, the craft of book-creation. (And as many would already be aware, calligraphy is not unique to the Christian monastic movements; a tradition of calligraphy is also found in Mahayana and Zen Buddhism.)

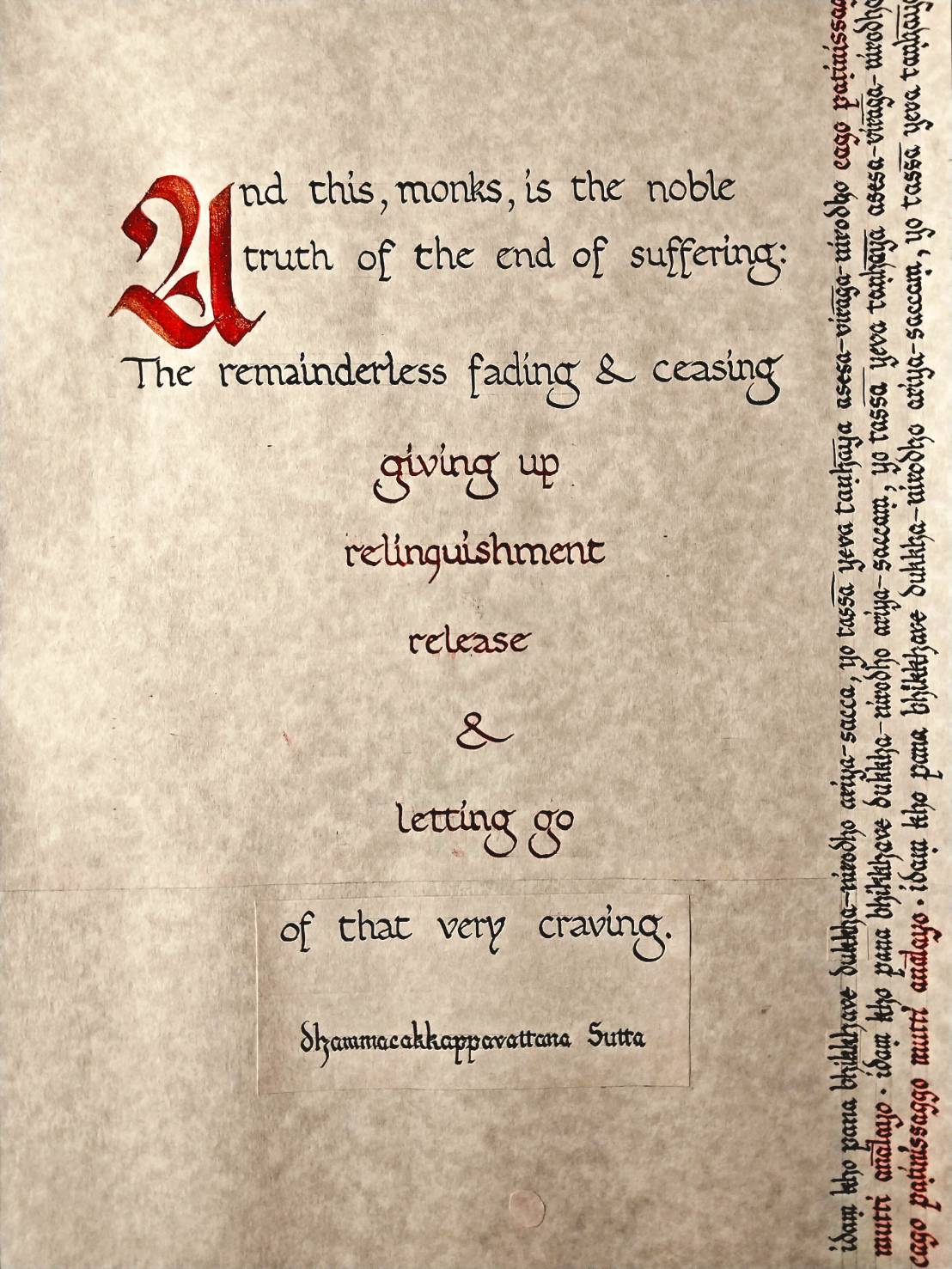

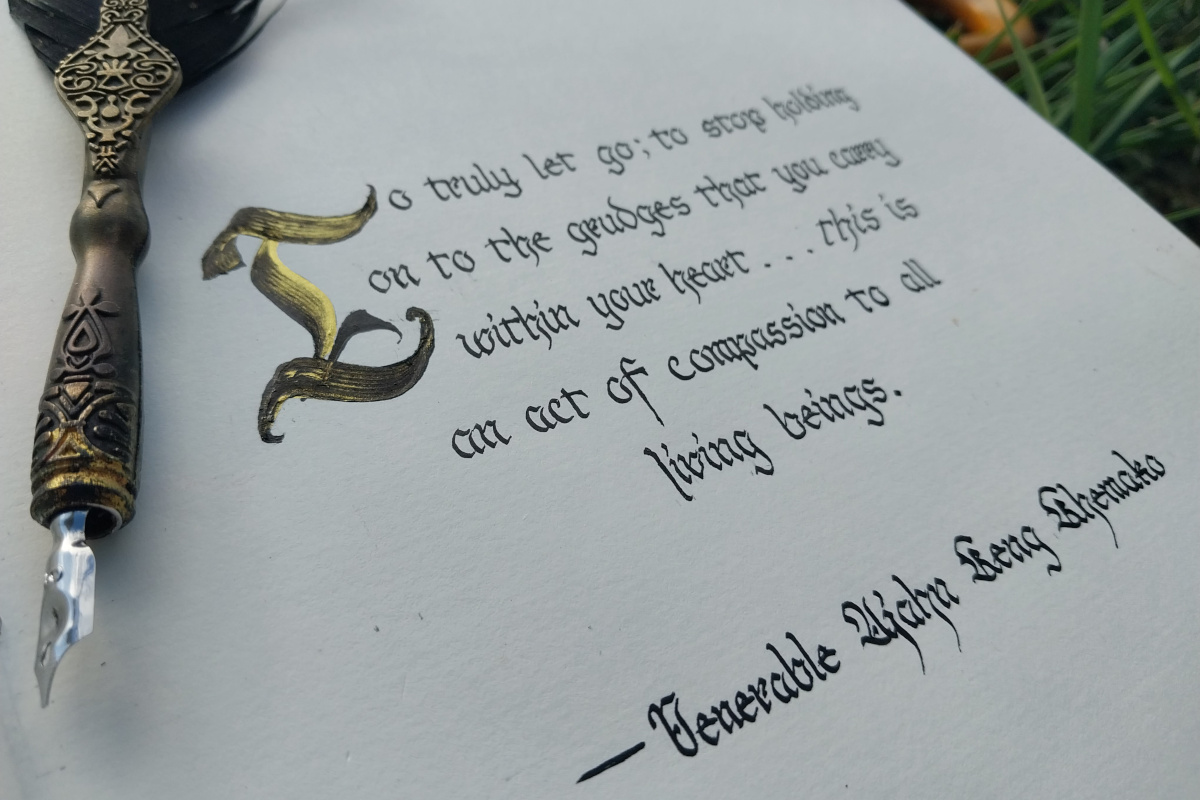

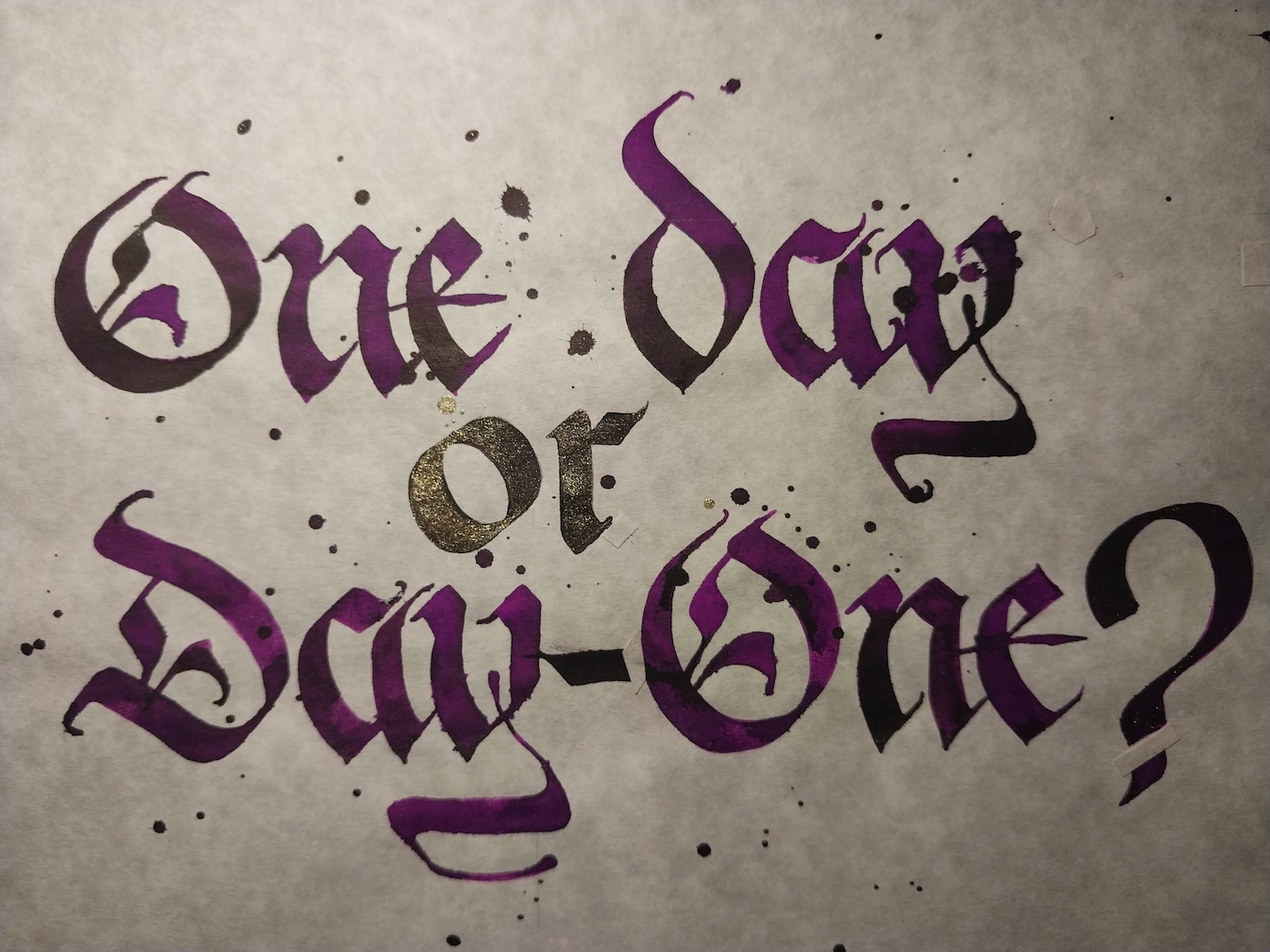

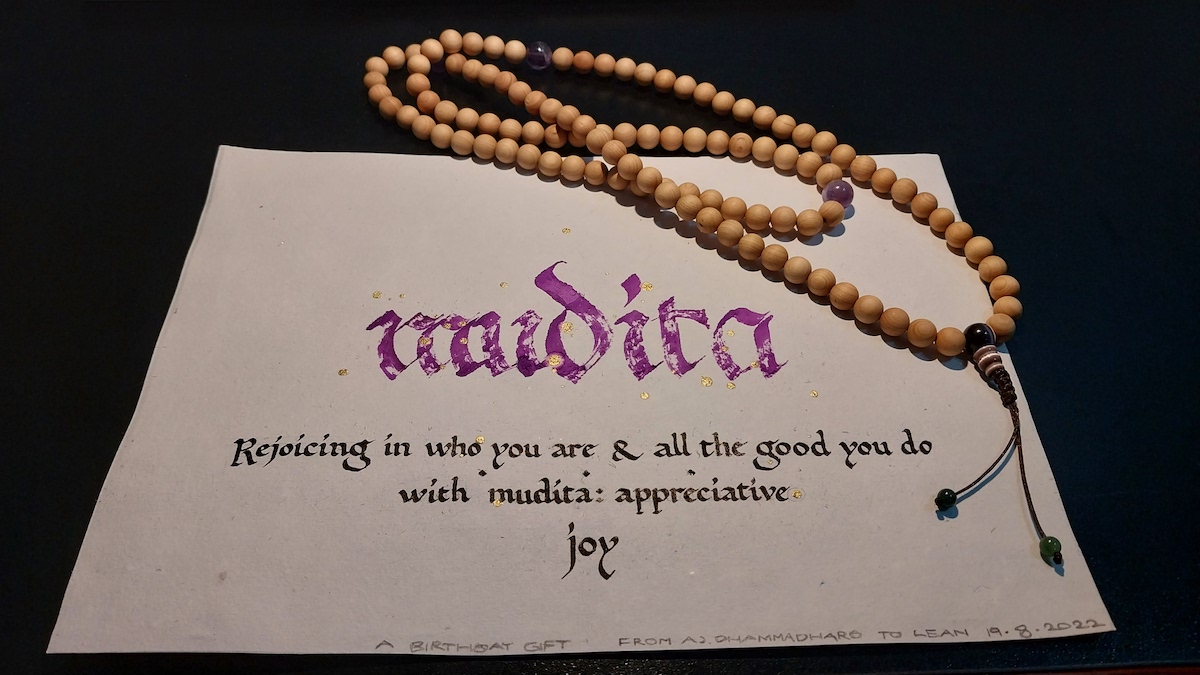

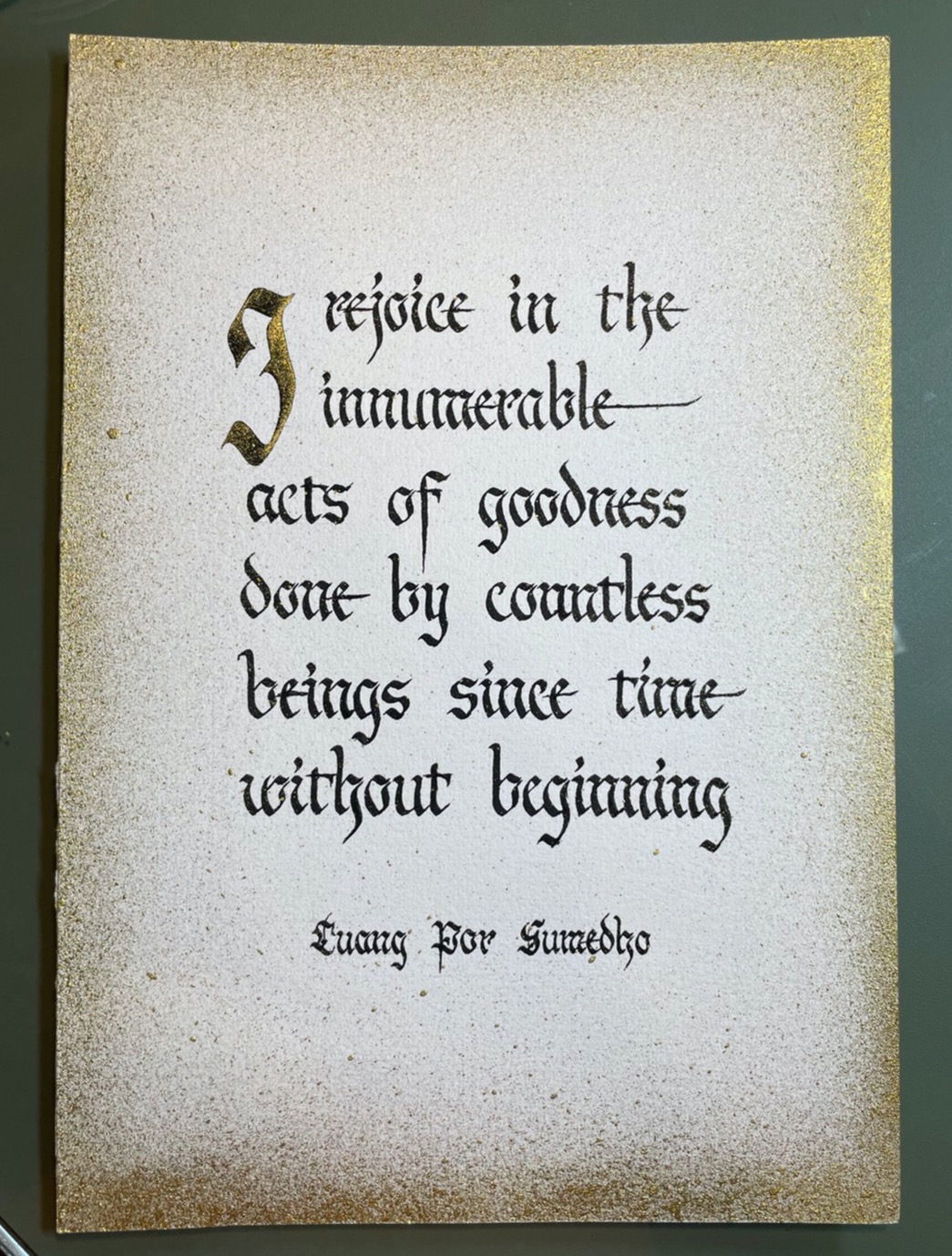

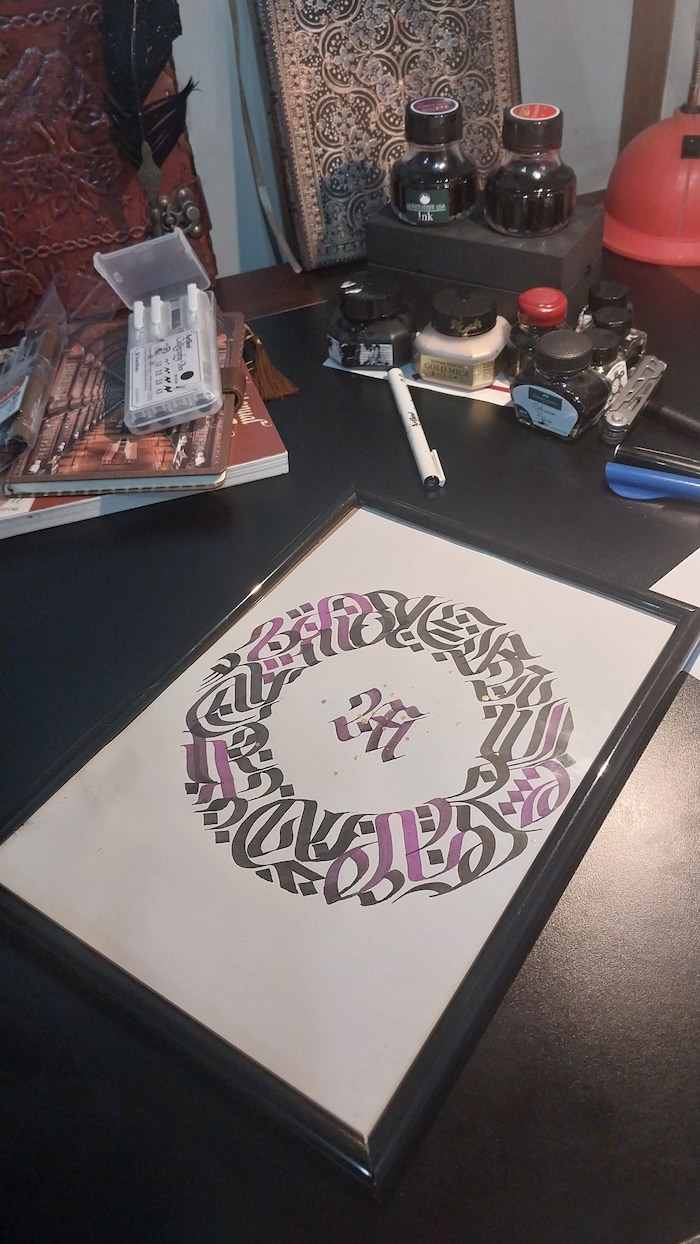

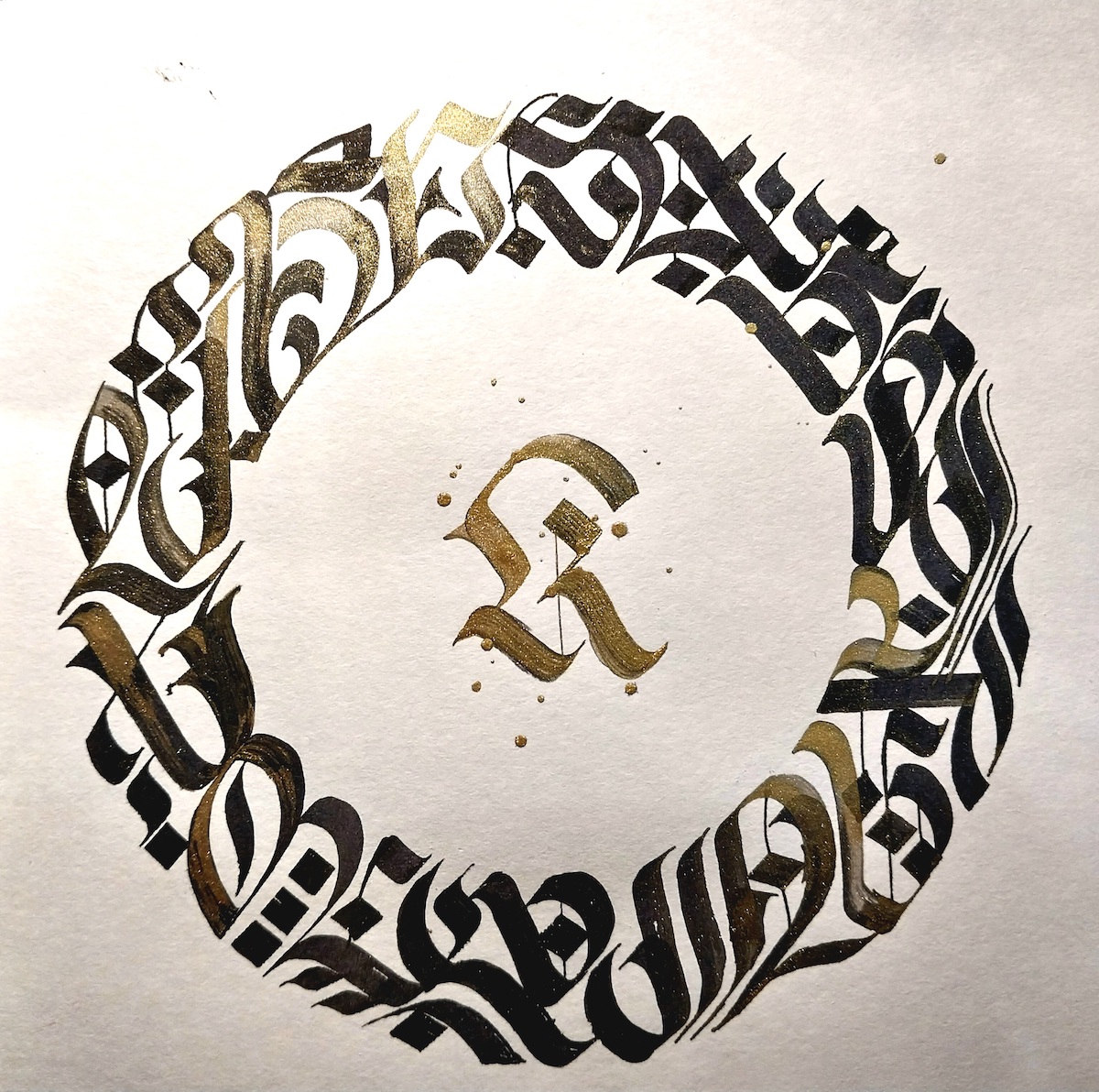

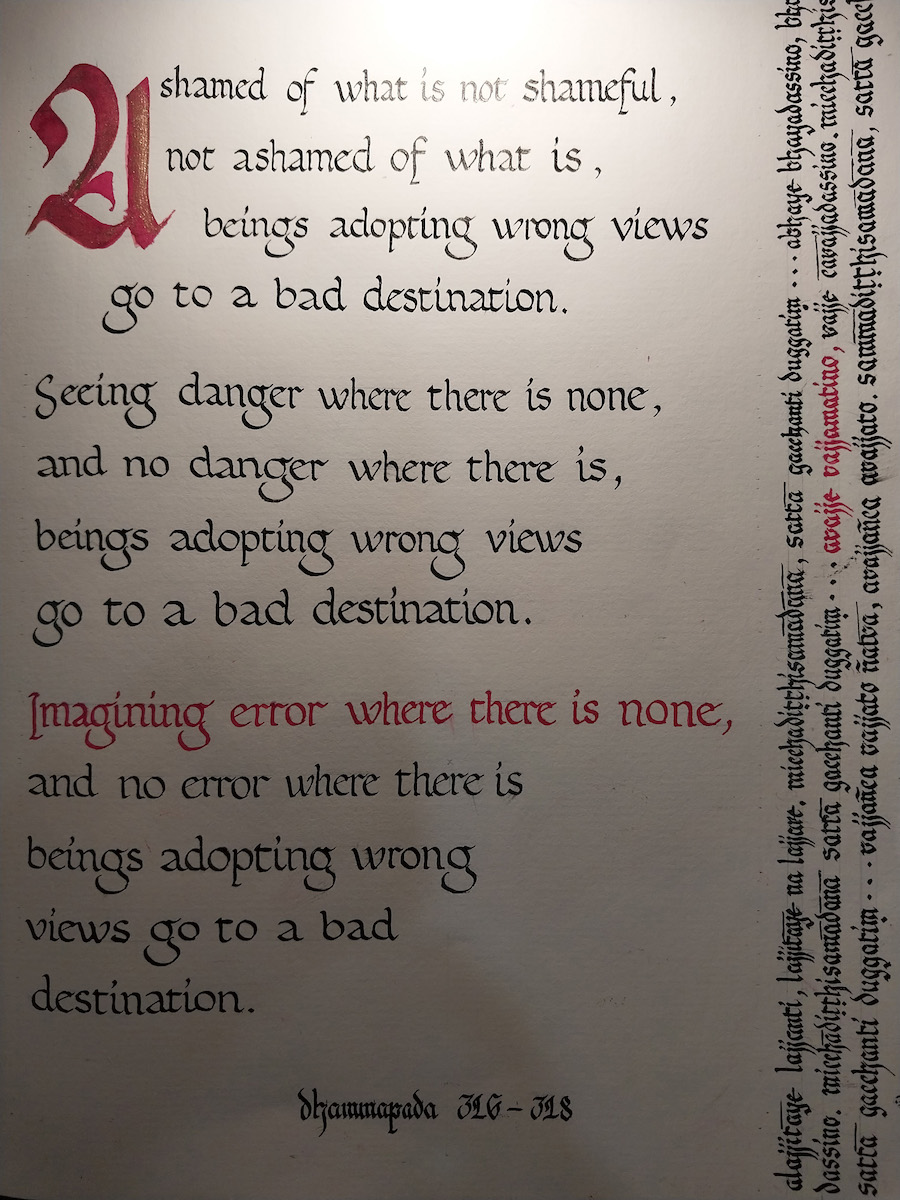

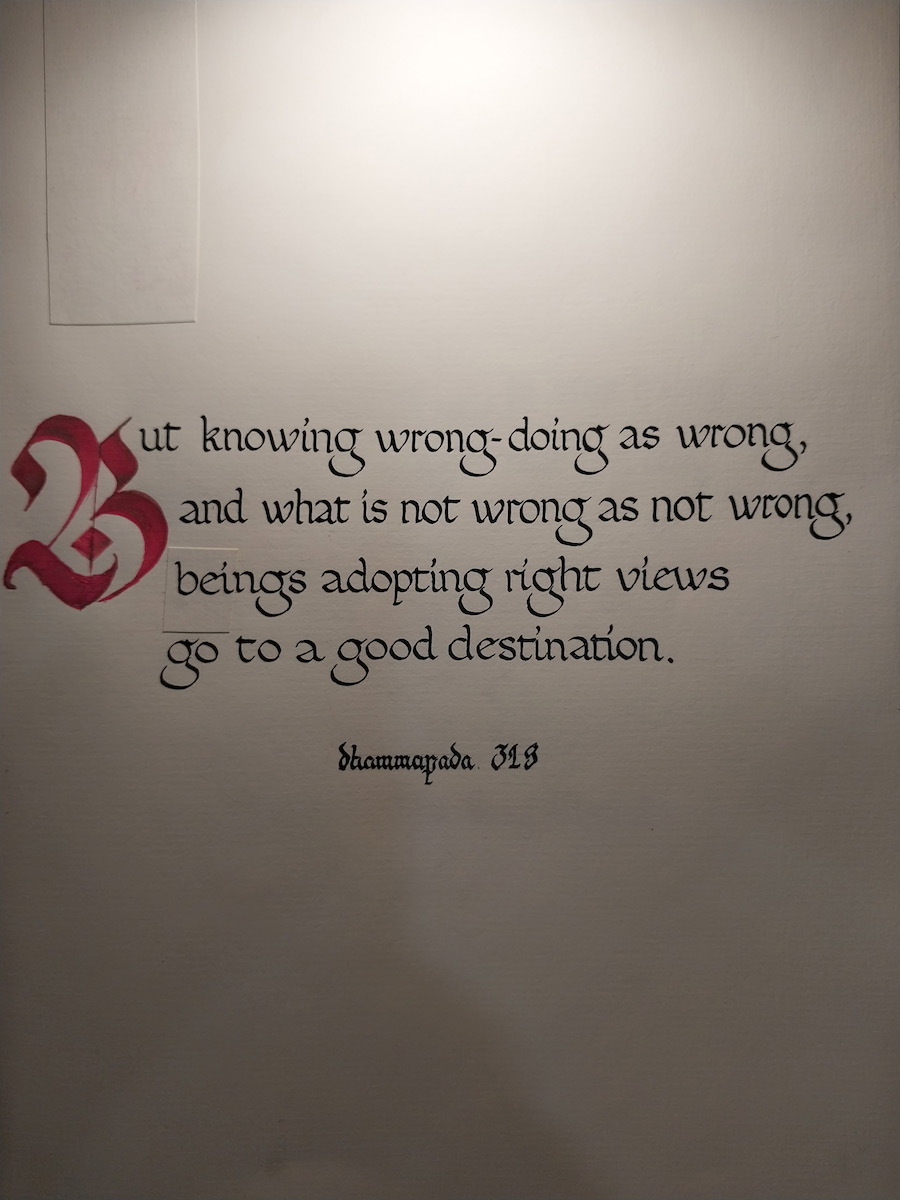

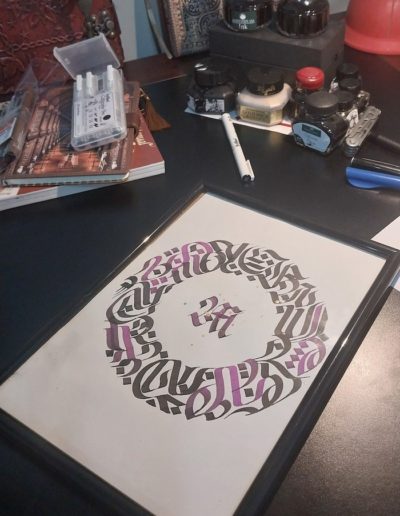

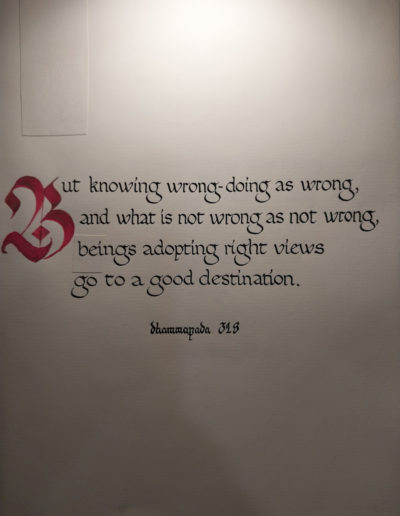

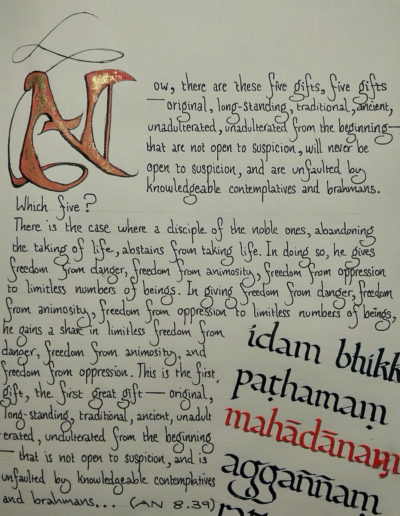

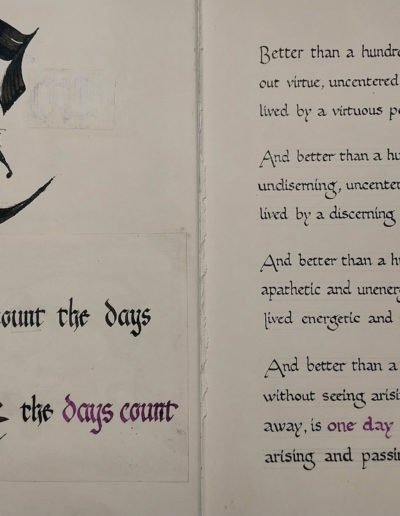

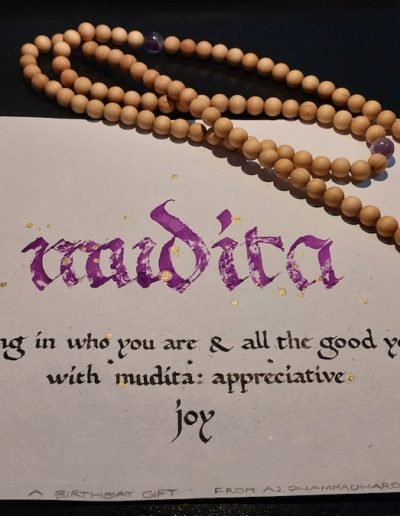

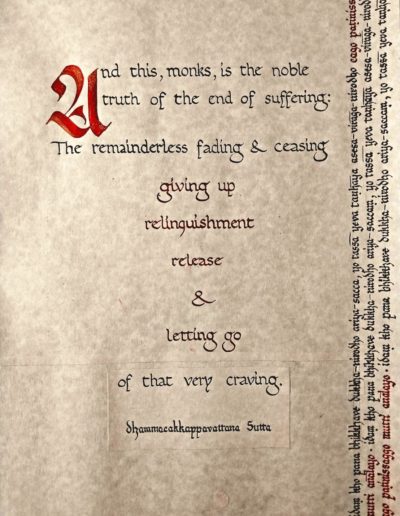

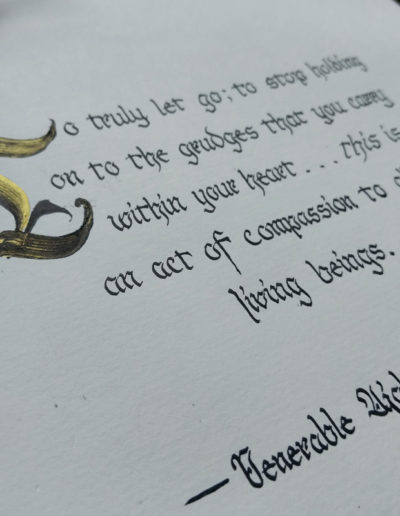

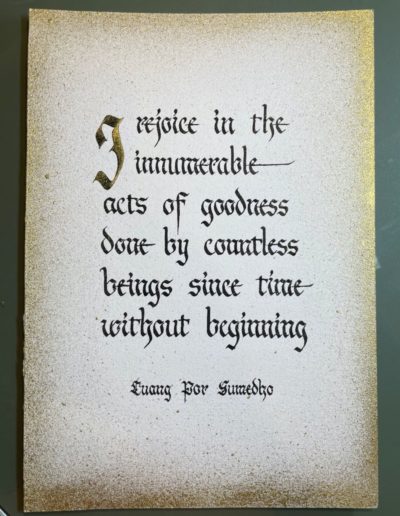

If it is straight Dhamma that I am doing—either from the Buddha or from any other Dhamma teacher—I use a script called “foundational hand” as it is clear and easy to read; I avoid embellishment or too much decorative element in the main text of a passage of Dhamma as it may render it illegible for some or distract attention from the meaning of the words. For Pali words I use what is called “Fraktur miniscule script” as it has an archaic edge to it—fitting for an ancient language, I think—but also quite clear and easy to read. For miscellaneous passages, quotes, or single words, I permit myself more creative flare.

Words have their limitations; they can only convey so much. But they they can still convey a lot. And when deployed with skill they can be very powerful. I hope some inspiration can be found in these ones.

– Ajahn Dhammadharo